A History of French Prints from the Fantastically French Exhibition at the Blanton with our very own AFA instructor, Blandine Nothhelfer.

Many great eras of design and artistic movement in Europe have come and gone, but none were as Fantastically French as the 16th through 18th centuries, when architects, landscapers, furniture designers, portrait artists and all manner of other artisans around the continent took part in the practice of reproducing their work in print. These pieces, we will learn about in this article, played profound formal and functional roles in these designers’ professions, influenced other artisans, and communicated enormous amounts of detail to contemporaneous viewers.

The Blanton Museum at the University of Texas currently showcases a full exhibition of French prints from those eras titled Fantastically French. I had the opportunity to both see the exhibition in person and to speak virtually with the Blanton’s Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings and European Art, Holly Borham. Below, Holly describes the exhibition in some detail and gives some background to some of the works. Our instructor Blandine Nothhelfer, who has a masters degree in Cultural Heritage Studies and worked in museums and arts institutions in France and Italy provides her expertise on the subjects as well.

We hope you enjoy this informative post on what is an exceptional art exposition. We encourage you to visit the Blanton this summer to see the exquisite art works in-person, and to join our future event that will explore symbols and details through the prints exhibited in Fantastically French.

A Celebration of Creativity

“The more you look at these works, the more details you see, and the more engaging they are.”

The exhibit is currently open to the public, and will be open until August 14, 2022. There are three galleries, each with different arrays of artisanal, artistic expression caught in print and the Blanton hosts public, in-person tours through the summer.

Holly Borham’s graduate work focused on German art of the 17th century with an interest in works on paper, which spans a lot of different time periods and geographies. She’s been at the Blanton for four years, and over time, working with art on paper has allowed her to work with material generally starting from 1450 going up through something that was made yesterday.

“The Blanton”, Holly told me, “has a really deep collection of French works on paper. As I was thinking about a show that would fit in well in our exhibition calendar–I was feeling during the pandemic that I wanted to show something that really celebrated human creativity and joy.

We have these French design prints, which are not usually what make the cut for ‘best of’ European works. Things that are in a design category often get overlooked, or they get put into a category that gets cut at the last minute. But the more you look at these works, the more details you see, and the more engaging they are. There is history involved, personalities, stories and portraits, but at the basic level, you can come in and just delight in these creative details.”

Holly explained that at the time the exhibition’s works were being published, France was trying to establish itself on the world stage–that the engravings and designs were part of an international affair: an exchange of ideas between prominent artisans from around Europe—they tried to elevate themselves by associating with and working with other countries. This exchange, the interest in these printed designs, and a quick look into the complex history of this period of art are discussed below by AFA instructor Blandine Nothhelfer.

Architectural Prints and Design in 16th-18th Century France

If the 15th century is the time of the Italian Renaissance, a prolific art movement that finds inspiration in the canons of Greek and Roman Antiquity, the 16th century is instead the time of the French Renaissance in which, at the image of Lorenzo de Medici, King Francis I (François 1er) sets a new model for generations of French monarchs till the Revolution in the end of the 18 th century: a great builder and patron of the arts.

From the castle of Fontainebleau, cradle of this new Renaissance, to the castle of Versailles two centuries later, kings will use architecture and design as a reflection of their power, making France a fashion hub for these arts. What role do the prints play in this story? When you want to tell all Europe that you are the most powerful person who builds the most beautiful things in a time when the internet and cameras are nonexistent, you fortunately can use printing from drawings made by artists to diffuse copies of your wonders.

Prints were not just a tool for propaganda, however. They were used for devotion or decoration, as common people couldn’t pay for an artist or a painting. They would decorate their walls with prints copying a famous painting, like we do with posters nowadays.

Most importantly, prints were essential for the formation of artists and architects. For instance, not everyone could travel to Italy to see the works of the great masters of Renaissance or the antique monuments of Rome. Thanks to the circulation of prints and drawings made by other artists, they could educate themselves on different styles, techniques, and fashions, as you can see in the exhibit at the Blanton.

In the 16th century, an innovation considerably changed the art of printing. Rather than carving into wood blocks, artists now use an acid to smoothly incise designs into metal plates. It was called ‘etching’, and it allowed for the creation of highly detailed works. Whether it was coincidence or good timing, this innovation in the 1540’s benefited the spread of a new artistic fashion completed at the very same time at the Castle of Fontainebleau, giving birth to a new art movement called Ecole de Fontainebleau (School of Fontainebleau).

Le Maniérisme and the School of Fontainebleau

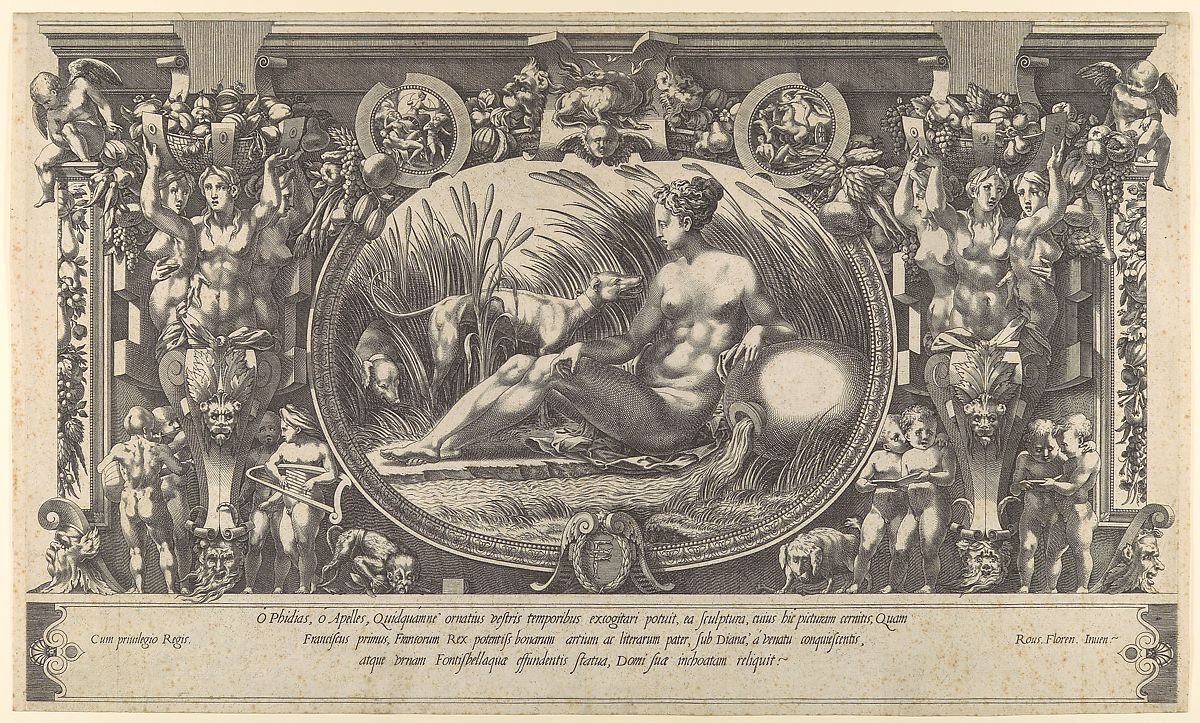

Nymph of Fontainebleau, copy by Pierre Milan and Rene Bovin featured in Fantastically French.

In 1528, King Francis I called some of the greatest Italian artists of the time to rebuild and decorate the Fontainebleau castle near Paris. Among them, Rosso Fiorentino and Francesco Primaticcio created a whole new style of interior design that will soon influence all of Europe. They introduce ornamentations and figures in stucco (1) that they mix with paintings (2), frescos (3), carved wood panels (4) and cartouche (5).

When the biggest part of their work was achieved in 1547, a few painters-etchers like Pierre Milan, Antoine Fantuzzi and Jean Mignon copied their compositions and decorations. Thanks to the new etching technique, they could reproduce every detail of the artworks. Some years later, these etchings circulated around all of Europe, which marked the beginning of the School of Fontainebleau, namely artists around France and Europe copying the artistic style of the castle.

Besides the decorative innovation, the artistic style of Rosso and Primaticcio is a French evolution of Mannerism. This artistic movement “in the manner” of the works of the great masters like Raphael paradoxically is a reaction to the Renaissance aesthetics of perfection. Mannerists reject the symmetry and balance to favor sinuous line, bodies that contort into S lines, artificiality, and unnaturally bright colors. They use mythological references, and their busy compositions overflow with details and symbols whose variety and complexity is almost grotesque. Mannerism will give birth to the Baroque movement.

French Classic Architecture and Rococo vs. Italian Baroque

Adam Perelle, La Salle des Festins, Versailles, published 1704, etching, 8 13/16 x 12 3/16 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, The Leo Steinberg Collection, 2002

Born in Italy at the end of the 16th century, Baroque architecture reached all of Europe in the 17th century. Inspired by mannerism, it presents curved lines, exuberance, heavy ornamentation, and dramatic effects. Two prints of church facades from Jean Le Pautre are a great illustration of this style.

In France however, Louis the XIV wanted to be emancipated from the Italian artistic hegemony. With some architects like Pierre Lescot and Philibert De l'Orme (whose architectural volume the Blanton has on display), he will come to create his own French architectural style that will make Versailles the new shining center for the arts in Europe, ousting Rome. This style is called French Classicism: the buildings and facades present a rigorous symmetry and straightness with a cleaner look, inspired by Greek and Roman temples. This style extends to the garden, which plays an important role in the life of the court. In Versailles, the art of landscape will reflect the supreme power of the “Sun King” over everything, including nature.

Gabriel Huquier, Panel of Ornament with Eight Figures and a Swing [La Voltigeuse], after Jean-Antoine Watteau, circa 1725, etching, 25 3/16 x 18 1/4 in. Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Jack S. Blanton Curatorial Fund, 2008

These ordered, straight and symmetrical gardens can be seen in many prints in the exhibition. For interior design though, it’s another story. The decoration heavy in gold and ornaments is very much inspired by the Baroque style. Nevertheless, a new style emerged in France in the 18th century: the Rococo. Like Baroque, Rococo is heavy in details and ornaments, but in a more delicate and feminine way. It prefers white over gold and uses a shell-shaped design for chandeliers and mirrors. While Baroque’s subjects are dramatic or violent, the Rococo is more frivolous and happier, depicting, for instance, pastoral scenes and landscape with the emblematic figure of the swing. You can see a very good example of this in the exhibition in the copy of a Jean-Antoine Watteau made by Gabriel Huquier. The French iconic style is a mix of Classicism and Rococo, two opposite extremes, yet very representative: we can think that Classicism embodies the rigidity of French monarchy while Rococo embodies the frivolousness of the French court.

What Blandine Loves About Fantastically French

I love this exhibition because a lot of prints have a great story to tell. For instance, this picture of a party in the garden of Versailles reminds me of fun anecdotes about how the French aristocrats that attended this very party were so numerous that they had to sleep in their carriages the whole weekend.

These are the kinds of things I like to talk about in my Art Conversation classes at AFA. What story can you find behind a piece of art that makes it more meaningful? Also, I think the portrait of the King of France Henri II, the son of Francis I, is very fun because the more you look at it, the more you see. Nothing is a coincidence; every detail tells us something about the king and what he wants you to know about him.

If you’d love to decipher this portrait, or other prints like it, you can join our future event that will explore symbols and details of the works exhibited in Fantastically French. Thanks for reading!

About the co-authors, Evan Bostelmann & Blandine Nothhelfer

Evan is the School Coordinator at the Alliance Francaise d’Austin. He has studied and taught French for 10 years. He spent time in Rouen, Normandie before moving to Austin in 2017, and has a passion for second language acquisition and for learning about others’ journeys through Francophone culture.

Blandine is an AFA instructor who grew up in France and is always seeking to make art and history fun for all. She has a master’s degree in Cultural Heritage Studies and worked conceiving education programs and events for museums and art institutions in France and Italy.